Amazon Buys Up Thousands of Acres As It Eyes Future Real Estate Needs

Amazon has quietly acquired thousands of acres across multiple regions, fueling speculation about its long-term real estate strategy. As e-commerce and logistics demands grow, Amazon’s large-scale land purchases could be a move to expand its fulfillment network, establish data centers, or position itself as a dominant player in commercial real estate.

However, concerns about corporate land speculation, potential zoning conflicts, and the long-term impact on housing markets and local economies are rising. This report dives into the motivations behind Amazon’s land grab and its implications for real estate markets and economic development.

Klean Industries Boardman, Oregon facility, is surrounded by $5 billion worth of Amazon data centers, and it is absolutely astonishing how fast Amazon deploys its capital.

Land Purchases Could Signal Shift by E-Commerce Giant

Amazon, the world’s biggest retailer, roiled the real estate world earlier this year when it said it would slow its pace of warehouse leasing and begin to sublet some of the tens of millions of square feet it had committed to as part of its pandemic-era expansion. But the fallout may not be as dire as some initially feared.

The pullback could suggest a strategic shift rather than a retreat from real estate. Over the past couple of years, the company has spent billions of dollars buying undeveloped land and properties for conversion to logistics centers, signaling it may plan to lease less and own more in coming years.

CoStar data shows that the company, which had more than $34 billion in cash on its balance sheet at the end of the first quarter, spent at least $2.3 billion to acquire dozens of properties totaling more than 5,000 acres since early 2020. That tally includes nearly 400 acres it has bought over the past three months. Amazon has scrapped or postponed large office and industrial projects nationwide and revealed plans to shrink its U.S. footprint of delivery and fulfillment centers by millions of square feet.

“In a perfect world, Amazon wants to control its real estate, especially the specialized and high-throughput facilities like final-mile delivery centers,” Paul Jones, managing director at Bridge Logistics Properties, a Utah-based Bridge Investment Group subsidiary, told CoStar News.

Prologis is developing Amazon’s biggest distribution center, a five-story, 4 million-square-foot warehouse in Southern California’s Inland Empire. (Samuel Evans/CoStar)

Amazon’s leasing slowdown comes as consumer confidence has slipped, inflation has climbed, and interest rates are rising. Its shares were down about 25% from the end of the first quarter through July 22, almost twice the drop of the S&P 500. Still, real estate professionals said Amazon’s step back from its aggressive industrial expansion has, in many cases, created opportunities for other users in what has become a historically tight industrial market across the country.

“Other users that Amazon has effectively crowded out will have an opportunity to come in,” said Bradley Tisdahl, CEO of Tenant Risk Assessment LLC. This firm provides tenant credit reports for commercial landlords. “The subleases could wind up being great for some of these smaller users or midsize companies that could benefit from their exposure to Amazon’s scale and reputation.”

National Strategy

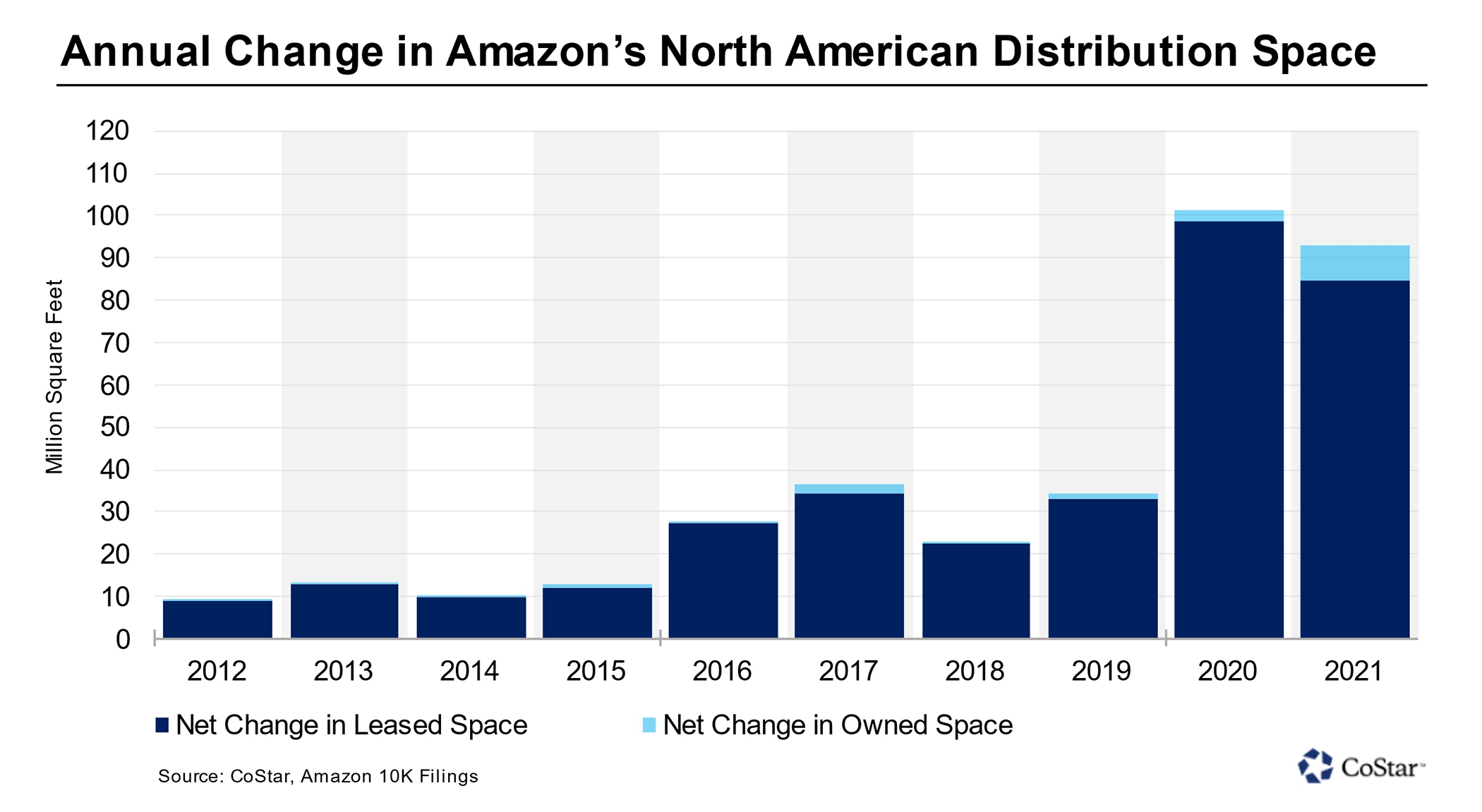

According to company filings, Amazon tripled the footprint of industrial and other commercial real estate it owns in North America from 2020 through last year.

At the end of 2019, it owned 5.6 million square feet of fulfillment, data center, and other commercial property, excluding offices and physical stores. According to its annual reports, the e-tailer increased to 8.4 million square feet in 2020 and doubled that last year to roughly 16.7 million square feet.

As part of its aggressive acquisition strategy, Amazon has scooped up vacant land and underused shopping centers, offices, and warehouses to build logistics centers as it moves to cut the cost of hiring outside developers and control a bigger slice of its vast warehouse and data center network.

“The opportunity to own key distribution warehouse assets not only puts them in control but also eliminates the ever-present double-digit rent growth,” said Abby Corbett, managing director and senior economist in CoStar’s market analytics group.

She noted that its leased square footage still dwarfs the company’s owned portfolio. The filings show that Amazon nearly doubled its leased fulfillment and data center space in North America to more than 370 million square feet from 2020 to the end of last year.

“As these assets become more and more expensive, highly automated and crucial parts of supply chains, it’s no surprise that Amazon and other retailers are saying, ‘I think I’d rather own,’ or are at least evaluating that decision more carefully,” John Morris, president of Americas industrial and logistics for CBRE, told CoStar News.

Amazon’s decisions to buy property rather than lease logistics space are “highly market- and submarket-dependent — whether Amazon has development partners that are slating up projects that appeal to it, and whether it feels the desire to control the space in that area” Corbett said.

With ownership comes Amazon’s ability to better develop and run its logistics facilities in regions such as Southern California, where community movements to ban or limit warehouse development near neighborhoods have taken root, Bridge’s Jones said.

“Amazon wants to control those sites because it’s getting so hard to get them entitled due to community and municipal opposition to traffic, trucks, and other issues,” he said.

Increased Ownership

If Amazon’s real estate strategy is shifting — the company has been mum on its intentions — it has a ways to go. The company owns less than 5% of its logistics and IT facilities in North America.

It has continued to buy property even as it trims space elsewhere, even rolling out so-called mega warehouses of up to 100 feet tall from New Jersey to Southern California.

The company last month acquired a 102-acre site north of Interstate 10 in Desert Hot Springs, a small city north of Palm Springs in Southern California’s Inland Empire, where city planners in March approved a warehouse that would be among the largest in the United States at 3.4 million square feet, according to city and public sale documents.

Also in June, Amazon bought 40 acres northeast of Minneapolis from local developer Rehbein Properties for what local media outlets reported is a planned 140,000-square-foot delivery center. And in April, Amazon Data Services, the company’s data center arm, bought 58 acres in Gainesville, a Northern Virginia suburb southeast of Washington, D.C.

Amazon has not disclosed its plans for Virginia land, next to another large parcel acquired by the e-commerce giant last year. However, Northern Virginia’s Prince William, Loudoun, and Fairfax counties, known as “Data Center Alley,” are among the nation’s most active regions for data center development.

In April, Amazon bought 70 acres of industrial land north of Tampa, Florida.

While it buys up real estate, the company has scrapped or postponed plans this year for industrial projects by other developers on its behalf that it would lease in such states as California, Iowa, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, according to CoStar News and various local news outlets.

The e-tailer recently walked away from talks with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey for one of the most significant proposed projects, an investment totaling more than $400 million to lease and redevelop two cargo facilities at Newark Liberty International Airport as an air freight hub.

Evolving Plans

Amazon did not address questions from CoStar News about the status of its active projects, its plans for the recently acquired land, or potential changes to its logistics real estate strategy. The company issued a statement similar to many other recent responses to media outlets inquiring about its real estate.

“Like all companies, we’re adapting to the availability of real estate and location of our customer demand, and we’re also constantly evaluating our approach based on our financials,” Amazon spokesperson Kelly Nantel said in the emailed statement. “Our plans continue to evolve, and we’re unable to confirm future builds or launches.”

The company said in April that it added too many warehouses and employees, nearly doubling the total square footage of its distribution network in the United States since the onset of the pandemic in early 2020. According to published reports, the company could offload up to 30 million square feet. CoStar data shows that about 8% of its U.S. industrial real estate holdings totaled 387 million square feet of leased and owned space at the end of last year.

Amazon could provide an update on its real estate activities when it releases second-quarter 2022 earnings on Thursday.

The company’s disclosure that it would shed warehouse space following a first-quarter earnings loss—its first since 2015—was among a litany of worrisome headlines this year, including rising consumer and business prices and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early March, which contributed to global supply chain disruptions.

However, analysts, including executives of CBRE, the world’s largest commercial real estate brokerage, and Prologis, one of Amazon’s biggest industrial landlords, have mostly dismissed the concerns.

CBRE’s Morris said the public and market reaction to Amazon’s pullback is overblown.

‘Very Strategic’

“This is not a fire sale,” he told CoStar. “They’re going to be very strategic about what capacities and facilities they delay. Their leadership says that they’ve built a supply chain for 2025. It’s just not 2025 yet.”

Morris said his market sources across the United States tell him that Amazon will shed less than 10 million square feet, mostly space under its Amazon Logistics warehouse platform, AMZL, from which the e-tailer makes last-mile deliveries to customers.

“I don’t know every deal in the country, but I’ve only heard of two unique subleasing deals going through,” Morris said. “There are a couple of sites they didn’t close on or are working out their options. But any development that is near complete they’re finishing, and any lease commitment, they’re leasing but maybe not occupying just yet.”

Chief Customer Officer Mike Curless said during the developer’s most recent earnings call that Prologis has received sublease inquiries from Amazon on just two of the 132 spaces it leases from the company and heard of only one Amazon space available for sublease during its calls with national brokerages last week.

“We have zero [Prologis spaces] in play,” Curless said. “What matters is what we’re seeing on the ground, and we’re not seeing much at all.”

Prologis officials have said Amazon is mostly only backing out of warehouse space it hasn’t yet occupied, hired workers for or outfitted with its high-tech robotic equipment, or at locations where it can quickly transfer logistics to neighboring facilities.

One of the Prologis buildings Amazon has subleased is a warehouse in Hayward, a San Francisco East Bay area city. Modular homebuilding startup Veev last month agreed to sublet the 500,000-square-foot building.

Logistics Firms Step Up

If Amazon strategically retreats from some industrial real estate obligations, it has created opportunities for others.

According to CoStar, the industrial vacancy rate nationwide is less than 4%. In the Los Angeles region, which includes the nation’s busiest port complex, the vacancy rate is below 2%, and in close-in areas, there are fewer than a half-dozen Class A spaces larger than 100,000 square feet available.

With Amazon on the sidelines, there is more room for other users to grab the space.

Tenant Risk Assessment’s Tisdahl said a mix of firms, from third-party logistics firms to large retailers like Walmart, are still playing catch-up to Amazon.

He added that with little to no space available in Los Angeles and other big logistics hubs, any Amazon sublease space should fill up quickly.

Since Amazon slowed its national warehouse leasing at the end of the first quarter, six other companies, including such retailers as Bed Bath & Beyond, Target, and Puma, have leased more square footage than the e-commerce giant, which has dominated industrial absorption since 2020, CoStar data shows.

Amazon appears to be giving up mostly smaller spaces, with more than three-quarters of Amazon-occupied industrial spaces listed as available for lease or sublet at less than 150,000 square feet, according to CoStar’s latest national industrial report.

Investigate the Impact of Amazon’s Real Estate Expansion

Amazon’s Land Grab: A Strategic Move or Corporate Overreach?

As Amazon continues its aggressive real estate expansion, the long-term effects on housing markets, industrial development, and local economies remain uncertain. Are we witnessing the future of logistics infrastructure or the latest wave of corporate land speculation?

What You Can Do:

✅ Stay informed – Monitor Amazon’s land acquisitions and their impact on property markets.

✅ Analyze the economic implications – Understand how corporate land ownership affects housing, taxes, and community growth.

✅ Hold big tech accountable – Demand transparency on Amazon’s real estate expansion strategies and zoning decisions.

✅ Share this analysis – Bring attention to the hidden consequences of large-scale land banking by global corporations.

Get Exclusive Insights on Corporate Real Estate Expansion!

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.